Lessons From Wolves by Jami Wright

INTRODUCTION

Gray wolves have long been the focus of a contentious battle in the Rocky Mountain West, where wolf populations were decimated due to habitat degradation and aggressive extermination tactics. However, the

species began their route to recovery in 1995 when, following the discovery by ecologists and biologists that restoring an apex predator to its natural habitat may increase local biodiversity, the federal government reintroduced the Gray Wolf

(Canis lupis) into the Northern Rocky Mountains. The ecological impacts of wolves continue to teach scientists about the complexity of wildlife conservation and management. Much of that complexity lies in human perceptions regarding the social impacts wolves have on people, which often represent deeper conflicts among cultures, usually relating to land use.

The effects of wolves on the ecosystem are neither clear nor immediate, or as extreme as anticipated, and this lack of clarity fuels wolf reintroduction debates. In Idaho, many residents support efforts to completely re-eradicate wolves from the state by any means necessary, but others support the re-establishment of wolf populations. Some even view the wolf issue as an opportunity to alter land management practices to foster either more development or more wildlife conservation. It's a topic that sparks passionate debate, and most people I spoke with had received physical threats simply because of their stance on wolves, regardless of whether they support eradication or reintroduction.

British anthropologist John Knight argues that wildlife conflicts are more often conflicts between people about wildlife, rather than actual conflicts between people and wildlife. Morgan Zedalis (2010) found the wolf to be an aspect of cultural identity for Idahoans. The survival or defeat of the wolf has come to symbolize the ability to access land in culturally specific ways, ultimately sustaining or depleting one's own culture. The sense of loss or endangerment of any culture is paired with the possible loss of irreplaceable traditional ecological knowledge, which may be vital to maintaining and improving biodiversity. Amid all of this, the wolf illuminates cultural disconnect within Idaho, pushing opposing groups further apart, or sometimes pushing them to cooperate in resource management.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE REINTRODUCTION

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service developed a plan in the 1980s mandating the reintroduction of the gray wolf in Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho under the stipulations of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The ESA was enacted in 1973 to counteract what had been the decimation of countless species for the purposes of economic development. Wilson (2006) summarizes the ESA as the culmination of the gradual transfer of wildlife management authority to the federal government and away from state control.

Throughout 1995 and 1996, a total of sixty-six gray wolves were captured in Canada and released in Idaho and Wyoming (

Defenders of Wildlife) and have since dispersed throughout most of Idaho, parts of Montana and Wyoming, with limited sightings in Washington and Oregon.

The public response to wolf reintroduction has been extreme and varied. Currently, many Rocky Mountain residents are angry about

decimated deer and elk populations and blame the reduced numbers on wolves.

Messier and colleagues (1995) believed that Yellowstone elk would decline significantly, more than thirty percent, following wolf reintroduction. However, Mech and Peterson (2003, p.159) 'predicted that wolf populations were unlikely to substantially affect deer and elk populations unless there were other contributing factors', like quality and quantity of habitat or high harvest by hunters. The Lolo Zone in north-central Idaho has been of particular concern. In the 1980s, elk numbers in the Lolo area were an estimated 16,000 animals; today, their numbers have dwindled to 2,178 (Idaho Fish and Game). Currently, Idaho Fish and Game is awaiting approval from U.S. Fish and Wildlife to reduce the estimated seventy-five to one hundred wolves in the Lolo region to twenty or thirty individuals through aerial gunning and trapping, despite scientists' claims that the herd has most likely declined because of poor habitat created by fire suppression throughout the previous century and the hard winter of 1996-97 (The Spokesman Review.)

Since the reintroduction, Yellowstone wolf biologist Doug Smith (2003, 2006) found that wolves might be indirectly responsible for an increase in plants and trees along riverbeds. The Ecology of Fear theory states that prey animals will change their behaviors due to a fear of predation. Thus, scientists believe that a fear of wolves would cause grazing ungulates (hooved animals) to spend less time lingering in riparian areas, leading to a recovery of willow and aspen trees that had been overgrazed by high populations of deer and elk. Healthy riparian zones filter out pollutants and control flooding and sedimentation throughout the watershed. Scientists have documented improvements in habitat for fish and beavers, and thus, quality of water since the reintroduction of wolves. (Smith et al., 2003, p.338). However, recent findings by Kauffman et al. (2010) suggest that aspen in Yellowstone National Park might still be declining and that the effects of wolves may differ throughout the park.

Reintroducing apex predators like wolves will undoubtedly play a role in changing local ecosystems, but there are many factors that contribute to these changes. Idaho's ungulate populations have declined since their all-time high fifteen years ago (Smith et al., 2003), but

2010 figures from a study conducted by Idaho Fish and Game found that wolves are not the sole culprit of this decline and from 2006 to 2009 hunters harvested more female elk than wolves killed. (Idaho Fish and Game). Doug Smith and colleagues (2003) note that fluctuations are normal and that wolf population peaks and declines lag behind those of prey. However, wolf extermination is a part of U.S. history and many people still believe it is a necessary component of wildlife management.

Only sixty years prior to the reintroduction, the gray wolf was all but extinct due to one of the most aggressive species eradications in U.S. history. Canis lupus inhabited all parts of the North American continent for at least 300,000 years prior to European colonization (Wilson, et al. 2000). Lopez (1978) estimated the population of gray wolves in the western United States and Mexico alone to have been at least several hundred thousand. The species' near-extinction was hastened by aggressive extermination policies enacted to protect domestic livestock and wild ungulates on behalf of the interests of ranchers and hunters during colonization. Predator control programs became a hallmark of the federal government's efforts to preserve the wilderness from 1900 to 1920 (Schullery 1995; Worster 1977). By 1931, three-fourths of the budget for the USDA Bureau of Biological Survey (now part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) was devoted to predator-control programs (Schullery 1995; Worster 1977). The National Park Service followed suit and instituted predator control efforts in the 1920s so that the gray wolf was eradicated from the continental western U.S. by the 1930s, with the exception of a small population in northern Minnesota (Wilson 2006). Wildlife management agencies were motivated to create a well-managed landscape that would contribute to the prosperity of the country, and efforts included the protection of game animals from predators.

According to Lopez (1978), wolvers, the men who killed wolves for a living during this time, were seen as heroes. They used poison, raided dens and strangled pups to death, clubbed wolves to death, and used traps to catch and kill wolves. A European wolfer in 1650 probably killed twenty to thirty wolves in a lifetime. An American wolfer in the 1800s most likely killed four to five thousand wolves in ten years. In Montana, 18,730 wolves were bountied for $342,764 of the state's treasury between 1883 and 1918. Consequential overpopulation of wild ungulates in the mid 1900s led to overgrazing of forests and grasslands and resulted in a re-evaluation of wolf management policies. Over the span of 150 years, Euro-Americans eradicated this predator to the brink of extinction for preying on domesticated livestock during American colonization. By the mid-1900s, the gray wolf was absent from the land with the exception of rumored howls in the northernmost states.

When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to reintroduce this predator into the Northern Rocky Mountains only sixty years later, Idaho enacted legislation prohibiting Idaho Fish and Game from participation in most wolf recovery efforts, including the expenditure of funds for related activities

(Idaho Legislature) . As the wolf release crept closer, members of Idaho congressional delegations urged Governor Phil Batt to use the National Guard or state police as a last resort to stop the reintroduction by force (Wilson,1999).

Federal officials did not need state support because the reintroduction took place on federal lands. This loss of state control over a natural resource management issue as significant as wolves caused a great deal of uproar in Idaho. When Idaho state officials refused to develop a state management plan, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service circumvented the state and approved the Nez Perce Tribe to carry out the wolf recovery program. The state's refusal to accept wolf reintroduction on any level enabled Idaho legislators to sustain the much-needed support of Idaho's livestock industry, which provides a large percentage of the state's annual revenue. Many Idahoans, including some livestock owners, supported Nez Perce wolf management because it enabled the state to continue its fight against the federally mandated reintroduction. Idahoans expected the Nez Perce to support wolves because of their cultural heritage and the Nez Perce sovereign nation did not have allies to upset. For many Idahoans at this time, the wolf issue did not belong to Idaho, it belonged to the Nez Perce. One livestock spokesperson stated in regards to Nez Perce management, "The state can continue to fight against the Endangered Species Act and fight the invasion of our sovereignty" (Wilson: 1999). To the Nez Perce people, the Wolf Recovery Plan was a long awaited opportunity for cultural revival.

THE WOLF AND THE NEZ PERCE PEOPLE

I sang one of our religious songs to welcome them back. Then I looked into the cage and spoke to one of the wolves in Nez Perce; he kind of tilted his head, like he was listening. That felt so good. It was like meeting an old friend.

Nez Perce Tribal Elder Horace Axtell, taking part in a 1995 wolf release (Littell, 2006:26).

In 1995, the Nez Perce Tribe fully embraced the opportunity to head Idaho's wolf recovery program. They addressed social issues by conducting seminars in rural Idaho in an effort to help citizens overcome fears and hostilities toward wolves and assisted federal officials in tracking, relocating, and removing wolves that attacked livestock. The state of Idaho took over wolf management in 2005, but Governor Butch Otter signed a formal Memorandum of Agreement granting the Nez Perce the right to continue managing wolves on tribal lands.

The Nez Perce management program served as a positive example for many tribes. It was the first time a tribe was able to take the lead role in the reintroduction of an endangered species. Much of the difficulty in managing public lands lies in determining who is authorized to make management decisions. Historically, Native Americans are not given the opportunity to participate in resource management, despite accumulated knowledge gained through millennia of experience and the passage of information down through generations of tribal members.

Wilson (1999) argues that the Nez Perce hold a set of values which straddle the divide between extractive and ecological. These factors contribute to tribes having a broader, more nuanced understanding of possible alternatives that may help move natural resource management decision-making in new directions. Nez Perce officials contend that native tribes possess a longer historical perspective and a deeper sense of permanence in their relationship with the land.

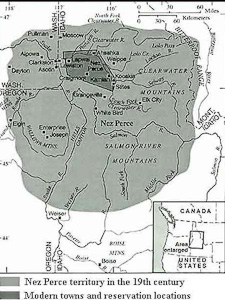

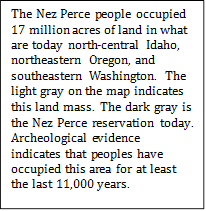

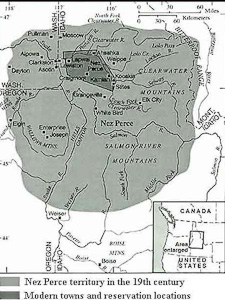

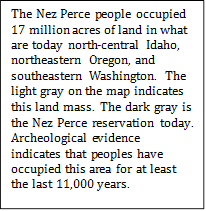

The Nez Perce people draw many parallels between their own historical experiences and those of the wolves. Prior to European colonization, both humans and wolves had occupied the same land for thousands of years, and in the wolf's case, hundreds of thousands. During this time, both survived the cycles of feast and famine through communal hunting practices while living in packs and bands. At the time of colonization, gray wolf numbers were estimated at several hundred thousand in the western United States (Lopez, 1978). Meanwhile, the Nez Perce had a significant, thriving community. With the onset of colonization, both were driven off the land upon which they depended for survival. This resulted in many lost lives and endangerment of culture and species. However, with the return of wolves to this area, many dormant aspects of Nez Perce culture have been revived.

THE WOLF AND NEZ PERCE REVITALIZATION

The Nez Perce people believe that animals are their ancestors, and that people still possess animal-like qualities today. Animals have unique abilities that people can attempt to develop, ultimately connecting the human animal to a larger ecosystem. In their history, the Nez Perce people were told by spirits, called wyakins, that one day they would be responsible for the protection of animals. The reintroduction of the wolf strengthens this belief and their cultural heritage.

A Nez Perce man, Chuck , explained that the wolf is a symbol of "the Indian way of life," and that the species' reintroduction has brought a renewed sense of empowerment to his people. "It symbolizes that the Indian people are coming back to that point again where we were strong and we thrived here, pre Euro-American settlement," he said. "At the height of our existence, we lived with wolves and grizzly bears; they are our brothers. We were at our strongest mentally and physically with these beings. Why wouldn't we want to try to go back to something like that?"

The wolf has served as a great teacher to the Nez Perce people, and despite its previous absence from the land, this legacy continues to live on today. Chuck said that "everything about wolves comes from that context (of being a teacher); they have to be treated as such. That is their role in our ecosystem." As we spoke about the wolf's role as a teacher, I came to understand an emptiness that Chuck and his people had experienced, and I realized that somewhere in that deep void lies a place for wolves.

Chuck feels that it is the duty of the Nez Perce people to work with state and federal agencies to stop what he describes as a relentless attack on the wolf. According to him, this attack is perpetuated by "the new generation of ignorant people. Anything that they feel is an aggressive animal or something that they've been taught can take a human life just shouldn't be here; it should be killed, right now." Chuck says that this belief reinforces the need for Indian people to spread the message that "we've lived with them since time immemorial and there are very rare instances of us ever being killed by wolves." This traditional ecological knowledge, that native peoples lived with wolves for thousands of years and have little remembrance of being attacked, is significant yet often overlooked.

When Chuck and I began to discuss the social conflicts surrounding this predator, the fact that wolves are a polarized social issue baffled him. He said, "It's amazing. There's this conflict that wolves are either really bad or really good. I mean I just don't see it like that." He feels that the United States sees wolves as critters that they can eradicate again in the future if they choose to. He continued, "It takes much more care than that to have respect for an animal, and so they really belong to us; they're our relatives."

Chuck feels strongly that it is the duty of the Nez Perce people to help provide wolves a place within the ecosystem. "More often than not, (that place is) inconvenient to human beings, such as ranchers and farmers, because they've never had to give and wolves have given everything -- who they are genetically, scientifically -- everything about them; they've been extirpated." The Indian request for non-Indians to provide wolves a place requires non-Indians to be unselfish, especially ranchers and farmers. He said it "means that there will be livestock depredations. There will be things that are in conflict, but how they live with them is up to that individual. And that is how the Indian people tell whether you are good or bad - your character."

Chuck noted that state and federal governments have historically protected ranchers with subsidies. Conservationists argue that the state gives ranchers inappropriate access to public lands for grazing. However, in this case, the state was unable to stop the federally mandated reintroduction of wolves in an attempt to protect ranchers, generating fear and anger in many ranchers and state officials alike.

THE BEEF WITH RANCHERS

An Idaho rancher named Joe explained to me that "a ranch is a good place to raise kids and teach them to care for animals. That's the biggest thing when you live on a ranch; you learn that you care." His point was made clear as I watched his two-year-old grandson play appropriately and respectfully with a puppy - not a common skill-set among many two-year-olds. "That's why it's so hard to watch them get killed like that," he said, referring to cattle he has lost to wolves.

Joe and his family had little experience with wolves prior to the reintroduction. He, and others in his community, had seen and heard what they thought were lone wolves prior to 1995. Joe felt confident that the wolves that were in his area initially were smaller and less aggressive than the wolves that live there now. "If there were local Rocky Mountain wolves, there aren't anymore," he said.

As we gazed out the back window of his home, he pointed to the exact location where wolves were first released just past his grazing cattle and beyond two mountain peaks. Six years after the reintroduction, he lost his first calf to wolves. At first, the pack consisted of just a male, a female and five pups. The next year there were twelve, and the following year the pack had increased to eighteen wolves. That year, he saw wolves every other day. Joe thinks the pack started to prey on his cattle after they had depleted local deer and elk populations.

Joe and his family have been taken aback by the violence of a wolf kill. Lately, the wolves have been going for adult cattle instead of the calves. This is unusual, and he thinks it's because the adults turn around to fight. When they turn to fight, one wolf latches onto the cow's nose and another onto its tail, and both rip and pull while others move in to gnaw at the cow's flanks. It appears as if the cow is eaten while it's still alive - a slow, brutal death that ranchers do not like to witness.

Joe agreed that more livestock are lost to disease and weather than to wolves, but it doesn't make the loss any easier to bear. His profit margin is small, and every little bit hurts. "You just hope you make money more years than you lose money." One year, he lost eleven animals, five of which just disappeared. "Typically you only find one in six wolf kills because they drag the calves to their dens." As a result of these attacks, Joe has observed what he described as a tremendous change in the behavior of his livestock. Relying on humans for protection, the frightened cows now bed down around their cabin, often coming in from very far away.

Joe and his family have had to change their own behavior as well. When a pack is stalking their cattle, either Joe or his son patrol the range every day at dawn and dusk. When the wolves start moving in at night, there isn't much they can do. "They're smart," Joes says. "Catching them out in your field is one thing, but trying to kill one is hard to do." Joe legally shot and killed one wolf that was stalking his cattle, and he has unsuccessfully shot at many more. He requested to have this pack taken out while wolves were still protected under the ESA. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declined, saying that they didn't want to shoot pups. Joe thinks they were dodging harassment from wolf advocates who argued against killing wolves on public lands.

The ESA has a bad reputation with ranchers, some of whom, like Joe, believe that the act is a tool the federal government uses to destroy and transform the West. Agriculture is the largest industry in Idaho. "Every dollar we make turns into seven for the state of Idaho," he added. "Why would you create so much strife? We don't need wolves for healthy ecosystems. Somewhere down the line, the government has to put production back on the line."

In 1993, a fisheries scientist from Portland, Oregon, working to protect Chinook salmon runs under the stipulations of the ESA, came to survey Joe's summer grazing land. The land was a grazing endowment leased to Joe by the state in conjunction with the ranch he purchased in the 1980s. The man from Portland surveyed Joe's land for two days. To Joe, he didn't seem to know a thing about cattle. Yet, "with the stroke of a pen" as Joe put it, he submitted papers that required Joe to relinquish grazing rights on 30,000 acres, or two-thirds, of public grazing land he had been using. The loss of income from this action led Joe to enter real estate and land development in order to supplement his income and continue ranching. Two years later, wolves were reintroduced only a few miles away from his house.

Joe readily admits that wolf activists create far more problems for him than actual wolves. He said that one man told him he would do everything he could to ruin him. People sometimes howl at his grazing cattle with the intention of spooking them, which often works. One night, someone opened one of the gates to an enclosure where his cattle were grazing and scared them out onto the highway. He recognized the car that was parked nearby and was almost positive he knew who it was responsible for the release. After his daughter and son-in-law were followed home one night from Joe's ranch, they decided not to get into ranching. Joe said, "These are people, not animals; they know what they are doing."

Joe wants more people to accept the idea that the wolf populations need to be controlled. He advocates poisoning wolves that kill livestock and supports Wyoming's shoot-on-sight policy, saying, "Even if we were able to shoot at every wolf we saw, it wouldn't make a dent in the population." Wyoming's aggressive state policy against wolves – mirrored by Joe's attitude – returned ESA protections to the species in August 2010, until Wyoming can adopt a sustainable management plan.

Many of the ranchers that I spoke with saw wolves as a threat to their way of life. However, it seems that the actual threat to their way of life is more about their diminished access to natural resources than the actual threat of wolves. Humans have fought over access to natural resources on a global scale for centuries, and the wolf has become a symbol of these conflicts.

The extreme hate invoked by this predator is disproportionate to the physical effects it has on human developments. The history between Euro-Americans and this predator is lethal and, arguably, irrational. In Medieval Europe, lycanthropy, or human-wolf shape-shifting, was considered to be a crime against God, punishable by death. Both people and wolves were routinely killed, much like witches, for this perceived sin. People believed that werewolves worked on behalf of the devil, killing livestock and murdering and raping people. During colonization in the United States, the wolf was thought of as a devil, and driven from a "Godly, well-kept landscape." Hopefully, we have evolved beyond the belief that the wolf is doing the devil's work.

THE VOICE OF CONSERVATION

There is still very much an anti-predator attitude in Idaho, so we go back and forth on this issue. Ultimately, we think in the big picture we've won; we've got wolves. We've won the battle and now we want them to like it. I mean, we've got so many conservation issues here. The fact that we have a species that's been de-listed and is thriving in Idaho, and we just don't like how they are being handled on an individual level, or even a pack-by-pack basis, is not significant ecologically. But because wolves are iconic, it's a great opportunity to do things right. To reconsider, when you're reinstating and reintroducing a keystone predator like wolves, the opportunity for learning and engagement of the public and for scientific research and for just a more holistic planning are tremendous. So, it's frustrating to see this opportunity being squandered. --A voice representing Idaho Conservation

In 2005, when the state of Idaho struggled to devise a wolf management plan motivated to delist the species, the nonprofit group Idaho Conservation stepped in to help the state develop an appropriate plan with appropriate wording that afforded Idaho a role in wolf management. However, after wolves were delisted and the state regained management authority, both state officials and Idaho Fish and Game have denied Idaho Conservation the ability to take part in developing management decisions.

The nonprofit had suggested wolf viewing as an income-generating activity. Dan, who is affiliated with Idaho Conservation, said, "People love it. They love tracking them and knowing what's going on. It's like a wolf soap opera." Prior to the August 2010 relisting of the wolf as an endangered species, Idaho had state control of wolf management and allowed a state-wide wolf hunt for the 2009-2010 hunting season. Dan proposed that the state set aside 10 percent of its land for wolf viewing activities. The other 90 percent would remain wolf-hunting zones. He argued that it would be a good control experiment to find out what would happen with elk and livestock depredations in these areas. Idaho Fish and Game told him that they already had their control experiment, with two categories. The first category was the previous ten- to fifteen-year period when no wolf hunting occurred; the second would be the current period, when wolf hunting would occur everywhere. He believed there was no reason to set it up as an experimental design managed with different zones. Idaho Fish and Game also told Dan, "'We are the Department of Fish and Game, not Fish and Wildlife. If your members want to have a Yellowstone-type experience, tell them to keep driving to Yellowstone.'"

Last year was Idaho's first wolf hunt since the reintroduction. The state sold 31,393 wolf tags (the necessary permit to kill a wolf) at $11.50 a piece, mostly to residents. Of around a thousand wolves known to live in Idaho, 183 wolves were legally killed. According to a draft Environmental Assessment written in August 2010, Idaho officials are discussing the use of more aggressive hunting tactics like trapping, snaring, and electronic calls used to bait wolves, as well as state-controlled sterilization and killing of pups (

USDA).The federal plan requires the state to maintain 150 wolves, a number which conservationists argue is dangerously low and drastically reduces genetic variability.

However, the largest cause of wolf mortality is lethal control by government agencies in response to livestock predation

(Defenders of Wildlife) In 2008, while still protected under the ESA, wildlife agents and ranchers killed 245 of the estimated 1,500 wolves in the Northern Rockies (Brown 2008). One such kill happened near Kalispell, Montana, where a pack of twenty-seven wolves, including two litters of pups, was under surveillance for killing livestock in the area. The pack had killed at least five cows, five llamas and a bull over the course of several months. Wildlife agents initially killed eight of the wolves and then decided to take out the remaining nineteen when the pack continued to hunt livestock.

The livestock industry has been integral in the financial and structural development of Idaho. Idaho ranchers and sheepherders pay taxes to the state for the public land on which they graze their animals. These taxes help support Idaho's educational institutions (

Idaho Government) . Idaho continues to depend upon, and determinedly protect, livestock owners because of their vital role in the state's economy. The reintroduction of wolves has been viewed by some in the state as a federal assault against livestock owners and the state of Idaho as a whole.

Groups such as (

Defenders of Wildlife) are devoted to working with ranchers to find non-lethal ways to stop wolf depredations, and they have experienced some success. More than 90 percent of Northern Rocky Mountain ranchers affected by wolves seek compensation from the organization. In the past twenty-three years, Defenders of Wildlife has given $1.4 million, allocated as a part of their budget, to ranchers for livestock killed by wolves. According to their website, "This program helps to reduce political opposition to wolf recovery by shifting the economic burden of livestock losses from the ranchers to wolf supporters." Initiating relationships between pro- and anti-wolf groups under the common goal of stopping wolf depredations is a major strength of the program. The Defenders of Wildlife livestock compensation program ended on September 10, 2010, and they will instead assist states in developing their own federally initiated and funded compensation programs.

The organization claims that wolf depredations account for less than 1 percent of livestock losses, and this includes confirmed, unconfirmed, probable, possible, and improbable depredations. These terms refer to the likelihood that the animal was killed or attacked by wolves, based on findings from an investigation. These investigations have been controversial because it can be difficult to know for sure if the animal was killed by wolves. Researchers at Defenders of Wildlife also investigate tactics that minimize livestock depredations, such as the most effective ratio of dogs to number and type of livestock to keep wolves away, as it is not always financially possible, or even effective, to have a person continually guarding livestock. They also install turbofladry night corrals, a relatively new technique that combines orange or red flags and electrified wire to fence in livestock and has been successful thus far in deterring wolves.

Jen, a Defenders of Wildlife employee, has noticed growing support for the methods from, third-, fourth-, and even fifth-generation ranchers in Idaho and throughout the Rockies. It has taken some time to get to this point, and assisting livestock owners in their acclimation to wolves is a slow process in comparison to the modern speed of life. It requires patience and perseverance, and not all livestock producers are open to working with Defenders of Wildlife.

At first, some people wouldn't even return Jen's phone calls, but the compensation method became a good way for her to get her foot in the door and begin relationships. When referring to one man she has been working with, Jen said, "He does not like wolves. He probably never will, although I have actually heard him call them beautiful before. He has stood up in front of a crowd of his peers, Idaho Wool Growers [Association], and told them that they can coexist with wolves, as long as we can manage them. We might disagree a little bit about how to manage them, but as long as we can manage them he feels that we can coexist. That was huge."

Jen loves working with the ranching community. "Honestly, I'd rather work with ranchers or farmers, anybody that's working with land. They've got their feet on the ground and have a certain strength about them that I think is really missing from what most of us get to have on a day-to-day basis. Good community to work with. We have a lot to learn from them."

RANCHING AND TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE

I don't think there are good and bad animals, just good and bad managers.

-Anonymous rancher from

Beyond the Rangeland Conflict: Toward a West That Works, by Dan Dagget

Many ranchers have traditional ecological knowledge acquired by working the same land for their entire lives and inheriting skills from previous generations that worked the same, or similar, land before them. For people who live on the land for multiple generations, maintaining the health of the land is of the upmost importance because it ensures their family's continued survival. The land becomes a part of them, and sometimes they can read its changes better than a visiting scientist.

Bev, a pro-wolf rancher, and her family have been ranching on the same Idaho land for 140 years, making this her family's ninth generation on the land. When first settling, their predecessors lived in caves on the property. Bev's family refers to historical oral and written accounts, left by their predecessors, regarding the condition and patterns of the land, how it was managed, and notable environmental changes. Equipped with this knowledge, Bev has noticed the disappearance of important land management practices among her neighbors, such as the ability to smell a handful of earth and detect which nutrients it needs.

These days, Bev manages her land with a combination of her family's traditional ecological knowledge and a system called holistic management, which was developed by the nonprofit organization

(Holistic Management International) . This organization is dedicated to managing land resources in partnership with nature to ensure the continued and improved health of the land. Although Bev has never had any wolf encounters, she has a vision for what she believes to be the integral role of wolves for healthy land and livestock management, which is in line with the holistic management approach.

Bev discussed the large herds of buffalo that once roamed across the western United States and the wolves that hunted them, forcing these ungulates into constant movement. This constant movement protected the land from being overgrazed and prevented riparian zones from becoming muddy bogs that were unable to support plant and animal life. Through their predatory actions, wolves played a vital role in maintaining clean water and healthy habitat.

Bev's historical account coincides with holistic management theory, which contends that with frequent movement, cattle, like buffalo, can't eat enough grass in one place to damage the root systems of plants. Strong roots usually make for strong plants, helping to create firm land, and thus, clean water. Cattle manure is a natural fertilizer for grazing land, which the cattle incorporate into the soil with their cloven feet. The land is often healthier with cattle or other ungulates as long as the animals don't exceed appropriate stocking rates, stray too close to riparian areas, or overgraze the land. Bev and her husband now move their cattle between small grazing plots on a daily basis, replicating how their cattle might move if there were wolves in her area.

Beavers also play an important role in ensuring clean water. An old family book written by Bev's relatives documents the extensive beaver dams along the river that runs through their property. Bev says they haven't seen beavers since fur trapping wiped them out last century. She believes beaver dams played a large role in adding structure to the river in the past. Dams slow and control the flow of water, which significantly reduces erosion. Since wolf reintroduction, Yellowstone scientists have found more beavers and beaver dams in Yellowstone National Park, perhaps connected to the returned presence of wolves (Smith et al., 2003, p.338). With improved riparian zones, beavers can now find the necessary materials to build dams and homes in which they breed.

Some people attribute Bev's pro-wolf stance to the lack of wolf encounters on her land. She notes that her family had endured some scary times when her safety was threatened because of her pro-wolf opinion. Since then, she keeps to herself on the issue, and her family chooses not to take a stand in public. If Bev and her family experience wolf depredations in the future, she wants the option to use lethal measures, but only if necessary. She looks forward to the lessons in land and water restoration associated with the reintroduction of wolves and feels that her duty is to ensure that the ranch's ecosystems are healthy for future generations of her family.

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Originally, ranchers and sheepherders were the most vocal about their opposition to the reintroduction for fear of lost livestock, which has turned out to be relatively minimal and controllable, but still difficult. Now, it is the sportsmen who have become more vocal about their anger regarding declined ungulate populations which are attributed to wolf depredation. Scientific findings fluctuate regarding these issues, but one thing is clear: there is no simple answer, as we discover many changing factors about the effects of wolves on an ecosystem. However, wolves are often the wrong party to place the blame upon.

The wolf invokes strong primal reactions within people, and many of the concerns surrounding this predator are actually human-created issues. As Joe mentioned, the wolf is only doing what its instincts drive it to do. People use the wolf as a symbol to attack points of view with which they disagree, as well as to teach others about culture and ecology. I propose that we must better understand the cultural factors, or human issues, affecting wildlife management in order to initiate the needed changes that will allow us to share space with the wolf and each other, ultimately protecting our natural resources for future use. David Quammen writes in Monster of God that alpha predators keep us acutely aware of our own membership within the natural world, deepening our reverence and humility. Wolf reintroduction in the Northern Rockies is an opportunity to better understand how we relate to the earth and to each other regarding the earth. The wolf reminds us of what we have lost and what we are losing while illuminating the need for us to make the necessary changes within in order to ensure our continued survival on the natural resources in which we depend.

Photos are copyright protected and are used by permission of Jami Wright. courtersy of the WERC. Photographs may not be reproduced without her permission.

WORKS CITED

Dagget, Dan 1995 Beyond the Rangeland Conflict: Toward a West that Works. Layton, Utah. The Grand Canyon Trust and Gibbs Smith Publisher.

Kauffman, MJ, JF Brodie, and ES Jules

2010 Are wolves saving Yellowstone's aspen? A landscape-level test of a behaviorally mediated trophic cascade. Ecology 91(9):2742-2755.

Littell, Richard 2006 Our brothers' Keeper. National Museum of the American Indian; celebrating native traditions & communities. 5(7):22-27.

Lopez, Barry 1975 Of Wolves and Men. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Mech, L. D., and R. O. Peterson

2003. Wolf–prey relations in Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation (L. D. Mech and L. Boitani, ed.). University of

Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois.

Messier, F., W. C. Gasaway, and R. O. Peterson

1995 Wolf-Ungulate Interactions in the Northern Range of Yellowstone: Hypotheses, Research Priorities, and Methodologies. Fort Collins (CO): Midcontinent Ecological Science Center, National Biological Service.

Schullery, P., and L. Whittlesey

1995 Summary of the documentary record of wolves and other wildlife species in the Yellowstone National Park area prior to 1882. In Ecology and Conservation of Wolves in a Changing World. S.H.F. L. N. Carbyn, and D. R. Seip, ed. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Circumpolar Institute.

Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America

1973 Endangered Species Act of 1973.

Smith, D. W. and Ferguson, G.

2006 Decade of the Wolf: Returning the Wild to Yellowstone. Guilford, Ct.: Lyons Press

Smith, DW, RO Peterson, and DB Houston

2003 Yellowstone after wolves. BioScience 53(4):330-340.

Wilson, Patrick Impero 1999 Wolves, Politics, and the Nez Perce: Wolf Recovery in Central Idaho and the Role of Native Tribes. Natural Resources Journal. 1999:39(543-564)

Quammen, David

2003. Monster of God. New York. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Worster, D.

1977 Natures Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Zedalis, Morgan

2010 The Return of the Wolf: The importance of wildlife in local identity among Central Idahoans and Nez Perce Tribe members. Master's Thesis, Conservation Anthropology, University of Kent.

"Animals", Nez Perce National Historical Park, accessed July 15, 2010,

http://www.nps.gov/archive/nepe/Education/SCHOOL2Aa_files/Education%20Guide.htm#Program_Introduction

"Gray Wolf Damage Management in Idaho for Protection of Livestock and other Domestic Animals, Wild Ungulates, and Human Safety", Environmental Assessment Draft, accessed September 6, 2010,

http://www.aphis.usda.gov/regulations/pdfs/nepa/idaho_wolf_ea.pdf

"Key Projects and Programs", Defenders of Wildlife Idaho Office, accessed September 6, 2010,

http://www.defenders.org/about_us/where_we_work/idaho_office.php

"Wolf Kills Increase", Wolf Center Blog, accessed September 6, 2010,

http://wolfcenter.blogspot.com/2008/12/wolf-kills-increase.html

"Defenders of Wildlife Launches Fund to Reduce Wolf Deaths", Defenders of Wildlife, accessed September 22, 2010,

http://www.defenders.org/newsroom/press_releases_folder/2000/12_21_2000_defenders_of_wildlife_launches_fund_to_reduce_wolf_deaths.php

"Idaho Wolf Conservation and Management Plan", accessed September 22, 2010,

http://species.idaho.gov/pdf/wolf_cons_plan.pdf

"State Trust Lands and Asset Management Plan", Land Assets, accessed September 22, 2010,

http://www.idl.idaho.gov/am/upd073008/Final_AM_Plan_wEFIB.pdf

"Idaho Fish and Game News", Causes of female elk mortality, accessed October 14, 2010,

http://fishandgame.idaho.gov/cms/news/fg_news/10/aug.pdf

"Idaho will ask feds for OK to kill Lolo wolves", The Spokesman Review, accessed October 17, 2010.

http://www.spokesman.com/stories/2010/aug/06/idaho-will-ask-feds-ok-kill-lolo-wolves/

Jami Wright, Writer, Photographer, Researcher

Jami is a graduate student completing her thesis for a master's degree in Cultural Anthropology at Western Washington University. Her thesis focuses on human-human conflicts surrounding wolves in Idaho. Born and raised in Fresno, California, the first eighteen years of her life instilled values pertinent to a grounded understanding, and appreciation for, cultural diversity. She completed her bachelor's degree in psychology at Cal Poly University, San Luis Obispo in California. During this time she gained fluency in Spanish while living abroad for one year in Chile and Spain. After completing her degree she moved to Idaho for eight years, nurturing her reverence for the mountains and wilderness. During this time she worked as a wilderness counselor/guide, finding great satisfaction in sharing and facilitating the use of the healing powers of the wilderness. It has been her dog Trooper who has opened her eyes to the remarkable intelligence of animals.

The effects of wolves on the ecosystem are neither clear nor immediate, or as extreme as anticipated, and this lack of clarity fuels wolf reintroduction debates. In Idaho, many residents support efforts to completely re-eradicate wolves from the state by any means necessary, but others support the re-establishment of wolf populations. Some even view the wolf issue as an opportunity to alter land management practices to foster either more development or more wildlife conservation. It's a topic that sparks passionate debate, and most people I spoke with had received physical threats simply because of their stance on wolves, regardless of whether they support eradication or reintroduction.

The effects of wolves on the ecosystem are neither clear nor immediate, or as extreme as anticipated, and this lack of clarity fuels wolf reintroduction debates. In Idaho, many residents support efforts to completely re-eradicate wolves from the state by any means necessary, but others support the re-establishment of wolf populations. Some even view the wolf issue as an opportunity to alter land management practices to foster either more development or more wildlife conservation. It's a topic that sparks passionate debate, and most people I spoke with had received physical threats simply because of their stance on wolves, regardless of whether they support eradication or reintroduction. decimated deer and elk populations and blame the reduced numbers on wolves.

decimated deer and elk populations and blame the reduced numbers on wolves.  In 1995, the Nez Perce Tribe fully embraced the opportunity to head Idaho's wolf recovery program. They addressed social issues by conducting seminars in rural Idaho in an effort to help citizens overcome fears and hostilities toward wolves and assisted federal officials in tracking, relocating, and removing wolves that attacked livestock. The state of Idaho took over wolf management in 2005, but Governor Butch Otter signed a formal Memorandum of Agreement granting the Nez Perce the right to continue managing wolves on tribal lands.

In 1995, the Nez Perce Tribe fully embraced the opportunity to head Idaho's wolf recovery program. They addressed social issues by conducting seminars in rural Idaho in an effort to help citizens overcome fears and hostilities toward wolves and assisted federal officials in tracking, relocating, and removing wolves that attacked livestock. The state of Idaho took over wolf management in 2005, but Governor Butch Otter signed a formal Memorandum of Agreement granting the Nez Perce the right to continue managing wolves on tribal lands.

Chuck feels that it is the duty of the Nez Perce people to work with state and federal agencies to stop what he describes as a relentless attack on the wolf. According to him, this attack is perpetuated by "the new generation of ignorant people. Anything that they feel is an aggressive animal or something that they've been taught can take a human life just shouldn't be here; it should be killed, right now." Chuck says that this belief reinforces the need for Indian people to spread the message that "we've lived with them since time immemorial and there are very rare instances of us ever being killed by wolves." This traditional ecological knowledge, that native peoples lived with wolves for thousands of years and have little remembrance of being attacked, is significant yet often overlooked.

Chuck feels that it is the duty of the Nez Perce people to work with state and federal agencies to stop what he describes as a relentless attack on the wolf. According to him, this attack is perpetuated by "the new generation of ignorant people. Anything that they feel is an aggressive animal or something that they've been taught can take a human life just shouldn't be here; it should be killed, right now." Chuck says that this belief reinforces the need for Indian people to spread the message that "we've lived with them since time immemorial and there are very rare instances of us ever being killed by wolves." This traditional ecological knowledge, that native peoples lived with wolves for thousands of years and have little remembrance of being attacked, is significant yet often overlooked.

In 2005, when the state of Idaho struggled to devise a wolf management plan motivated to delist the species, the nonprofit group Idaho Conservation stepped in to help the state develop an appropriate plan with appropriate wording that afforded Idaho a role in wolf management. However, after wolves were delisted and the state regained management authority, both state officials and Idaho Fish and Game have denied Idaho Conservation the ability to take part in developing management decisions.

In 2005, when the state of Idaho struggled to devise a wolf management plan motivated to delist the species, the nonprofit group Idaho Conservation stepped in to help the state develop an appropriate plan with appropriate wording that afforded Idaho a role in wolf management. However, after wolves were delisted and the state regained management authority, both state officials and Idaho Fish and Game have denied Idaho Conservation the ability to take part in developing management decisions.

Many ranchers have traditional ecological knowledge acquired by working the same land for their entire lives and inheriting skills from previous generations that worked the same, or similar, land before them. For people who live on the land for multiple generations, maintaining the health of the land is of the upmost importance because it ensures their family's continued survival. The land becomes a part of them, and sometimes they can read its changes better than a visiting scientist.

Many ranchers have traditional ecological knowledge acquired by working the same land for their entire lives and inheriting skills from previous generations that worked the same, or similar, land before them. For people who live on the land for multiple generations, maintaining the health of the land is of the upmost importance because it ensures their family's continued survival. The land becomes a part of them, and sometimes they can read its changes better than a visiting scientist. CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION Jami Wright, Writer, Photographer, Researcher

Jami Wright, Writer, Photographer, Researcher