Chronic Wasting Disease highlights underlying dysfunction in wildlife policy

Apri 27, 2018; Erik Molvar

Erik Molvar is a wildlife biologist and Executive Director of Western Watersheds Project, a nonprofit environmental conservation group dedicated to protecting and restoring watersheds and wildlife throughout our western public lands.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department is finally trying to come to grips with the spread throughout the state of Chronic Wasting Disease, a brain disease caused by a prion – or mutant protein – much like mad cow disease. It results in the slow wasting of infected animals as they grow listless, drool and eventually die. WGFD’s initial recommendations to limit the disease are reportedly to: (1) reduce artificial wildlife feeding stations, (2) issue more mule deer buck hunting tags and fewer doe tags and (3) change hunting seasons.

Mule deer bucks seem more susceptible to chronic wasting disease.

If you’re a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. And if you are a game and fish agency, there is a tendency to try to “manage” wildlife problems through more or different patterns of hunting tags and seasons. But this approach ignores a more promising solution – allowing native predators to take care of the problem. In this case, wolves and coyotes are better suited than human hunters to cut the disease out of the deer, elk, and moose herds because they naturally focus on culling the weak and the sick from the herd.

DOCUMENTATION OF CHRONIC WASTING DISEASE IN THE USA

DOCUMENTATION OF CHRONIC WASTING DISEASE IN THE USA

Coyotes and wolves, the deer family’s natural predators, offer a cleaner solution. But Wyoming state agencies, the agriculture industry, and their federal partners, have been at war with these real Wyoming natives for more than a century.

Coyotes are intentionally exterminated by the thousands each year in Wyoming. A federally agency cynically named Wildlife Services is the main culprit, engaging in aerial gunning, lethal trapping, the barbaric practice of burning coyote pups alive in the dens, and the use of poisons including the notorious M-44 “cyanide bomb.” The state Department of Agriculture and local ag extension services also are complicit in the annual coyote killing spree.

Coyotes are intentionally exterminated by the thousands each year in Wyoming. A federally agency cynically named Wildlife Services is the main culprit, engaging in aerial gunning, lethal trapping, the barbaric practice of burning coyote pups alive in the dens, and the use of poisons including the notorious M-44 “cyanide bomb.” The state Department of Agriculture and local ag extension services also are complicit in the annual coyote killing spree.

Conservation and wildlife advocacy groups petitioned Wildlife Services and the Wyoming Department of Agriculture to stop using M-44s statewide last year after a family had two of its dogs killed by them near Casper, but today, even after the first human fatality from an M-44 this past February (Dennis Slaugh, a rockhound who lived in Green River, Utah), both state and federal agencies insist on continuing to use this dangerous and indiscriminate type of land mine.

Pause

Current Time0:00

/

Duration Time0:00

Stream TypeLIVE

Loaded: 0%

Progress: 0%

0:00

Fullscreen

00:00

MuThe only thing that all this coyote slaughter accomplishes is to break up packs so that more coyotes – not just the alpha pair – breed. This results in more coyotes, but alone or in pairs instead of larger packs that could take down a deer and help cull mule deer infected by M-44s.

Realistically, coyotes aren’t effective elk or moose predators, but the State of Wyoming has a dysfunctional policy that prevents wolves from fulfilling their natural role as predators of these larger prey species. By declaring all wolves outside a narrow band of wilderness surrounding Yellowstone to be “predatory animals” and subject to unlimited killing without bag limits, seasons, or even a valid hunting license, Wyoming engages in state-sanctioned extermination of any wolf that ventures away from the Yellowstone region and into the rest of the state. And inside the “trophy management zone,” Wyoming Game and Fish Department has set aggressive targets on trophy wolf killing in the lands surrounding Yellowstone. As a result, wolves cannot perform their natural ecological function of minimizing disease in elk, deer, and moose herds across the vast majority of Wyoming.

While it would be foolish to expect human hunting to tackle the widespread and pervasive CWD problem in Wyoming, wolves and coyotes are tailor-made for the job. The State Game and Fish Department should be taking a leadership role in re-thinking our human relationship to native predators, so we can stop getting in our own way and start facilitating natural solutions to the chronic wasting disease epidemic.

While it would be foolish to expect human hunting to tackle the widespread and pervasive CWD problem in Wyoming, wolves and coyotes are tailor-made for the job. The State Game and Fish Department should be taking a leadership role in re-thinking our human relationship to native predators, so we can stop getting in our own way and start facilitating natural solutions to the chronic wasting disease epidemic.

WGFD also has highlighted wildlife feeding stations as a main threat in the spread of chronic wasting disease. But one of the biggest perpetrators of these feeding stations is Wyoming Game and Fish Department itself, through its operation of 23 elk feedgrounds surrounding the Yellowstone ecosystem, which lure thousands of elk away from their natural winter ranges (many of which are now private ranchlands) and concentrating them in unnatural densities. Western Watersheds Project, the Sierra Club, and others saw the catastrophic potential of CWD entering the Yellowstone elk herds, and sued to end this practice.

Killing or driving off native wildlife for the benefit of ranchers or hunters, or just to assuage irrational fears among the general public, is woven deep into the dysfunctional custom and culture of Wyoming. This CWD epidemic offers an opportunity for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department to teach us a little humility, and begin to reverse a century and a half of hubris and delusions that through the management of bag limits and hunting seasons we can successfully manipulate complicated natural systems to achieve a healthy and ecologically sound result.

The path forward is clear – close the elk feedgrounds and allow the deer family’s natural predators to repopulate and re-form their natural pack structures so they can cull infected deer, elk, and moose. Today, WGFD is asking the right questions, and pointing their recommendations in the right direction. Now they just need to plow ahead through the opposition of vested political interests to bring this effort to its logical conclusion – closing feedgrounds and restoring native predators. In a state like Wyoming, that would be no small achievement.

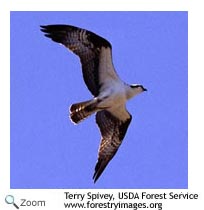

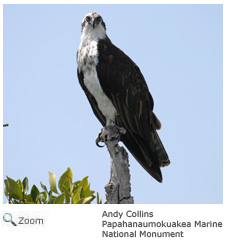

The osprey is found on every continent, except Antarctica. In North America, the osprey breeds from Alaska, north-central Canada, and Newfoundland south to Arizona and New Mexico . It is also found along the Gulf, Atlantic, and Pacific Coasts. It winters from the southern United States south to South America.

The osprey is found on every continent, except Antarctica. In North America, the osprey breeds from Alaska, north-central Canada, and Newfoundland south to Arizona and New Mexico . It is also found along the Gulf, Atlantic, and Pacific Coasts. It winters from the southern United States south to South America.