There comes a time in life for every bird to spread its wings and leave the nest, but for gray catbirds, that might be the beginning of the end. Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute scientists report fledgling catbirds in suburban habitats are at their most vulnerable stage of life, with almost 80 percent killed by predators before they reach adulthood. Almost half of the deaths were connected to domestic cats.

Urban areas cover more than 100 million acres within the continental United States and are spreading, with an increase of 48 percent from 1982 to 2003. Although urbanization affects wildlife, ecologists know relatively little about its effect on the productivity and survival of breeding birds. To learn more, a team of scientists at SCBI's Migratory Bird Center studied the gray catbird (Dumatella carolinensis) in three suburban Maryland areas outside of Washington, D.C.—Bethesda, Opal Daniels and Spring Park.

The team found that factors such as brood size, sex or hatching date played no significant role in a fledgling's survival. The main determining factor was predation, which accounted for 79 percent of juvenile catbird deaths within the team's three suburban study sites. Nearly half (47 percent) of the deaths were attributed to domestic cats in Opal Daniels and Spring Park. Scientists either witnessed the deaths or determined that they were cat-related by the condition of the fledgling's remains, such as a decapitated bird with the body left uneaten—defining characters of a cat kill. The researchers did not detect domestic cats during predator surveys in the third suburban study site, Bethesda.

"The predation by cats on fledgling catbirds made these suburban areas ecological traps for nesting birds," said Peter Marra, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute research scientist. "The habitats looked suitable for breeding birds with lots of shrubs for nesting and areas for feeding, but the presence of cats, a relatively recent phenomenon, isn't a cue birds use when deciding where to nest."

Technology made tracking the fledgling catbirds possible. The team fitted 69 fledglings with small radio-transmitters. Scientists tracked each individual and recorded its location every other day until they died or left the study area. This detailed type of field research was very limited until recently when transmitters were made small and light enough for songbirds.

Tracking the fledglings revealed that the vast majority of young catbird deaths occurred in the first week after a bird fledged from the nest. This was not surprising to the team, given that fledglings beg loudly for food and are not yet alert to predators—making fledglings in suburban environments particularly prone to visual predators such as domestic cats. Domestic cats in suburban areas that are allowed outside spend the majority of time in their own or adjacent yards, so they are likely able to intensely monitor, locate and hunt inexperienced juvenile birds. The researchers found that rats and crows were also significant suburban threats to fledgling catbirds.

"Cats are natural predators of not just birds but also mammals—killing is what they are meant to do and it's not their fault," said Marra. "Removing both pet and feral cats from outdoor environments is a simple solution to a major problem impacting our native wildlife."

The scientists' findings were published in the Journal of Ornithology, January 2011.

The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute serves as an umbrella for the Smithsonian National Zoological Park's global effort to understand and conserve species and train future generations of conservationists. Headquartered in Front Royal, Virginia, SCBI facilitates and promotes research programs based at Front Royal, the Smithsonian's National Zoo in Washington, D.C., and at field research stations and training sites worldwide.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Species Eradication Backfires Big Time

cbsnews.com

Michael Casey; Asso. Press

It seemed like a good idea at the time: Remove all the feral cats from a famous Australian island to save the native seabirds.

But the decision to eradicate the felines from Macquarie island allowed the rabbit population to explode and, in turn, destroy much of its fragile vegetation that birds depend on for cover, researchers said Tuesday.

Removing the cats from Macquarie "caused environmental devastation" that will cost authorities 24 million Australian dollars (US$16.2 million) to remedy, Dana Bergstrom of the Australian Antarctic Division and her colleagues wrote in the British Ecological Society's Journal of Applied Ecology.

"Our study shows that between 2000 and 2007, there has been widespread ecosystem devastation and decades of conservation effort compromised," Bergstrom said in a statement.

The unintended consequences of the cat-removal project show the dangers of meddling with an ecosystem - even with the best of intentions, the study said.

"The lessons for conservation agencies globally is that interventions should be comprehensive, and include risk assessments to explicitly consider and plan for indirect effects, or face substantial subsequent costs," Bergstrom said.

Located about halfway between Australia and Antarctica, Macquarie was designated a World Heritage site in 1997 as the world's only island composed entirely of oceanic crust.

It is known for its wind-swept landscape, and about 3.5 million seabirds and 80,000 elephant seals migrate there each year to breed.

Authorities have struggled for decades to remove the cats, rabbits, rats and mice that are all nonnative species to Macquarie, likely introduced in the past 100 years by passing ships.

The invader predators menaced the native seabirds, some of them threatened species. So in 1995, the Parks and Wildlife Service of Tasmania that manages Macquarie tried to undo the damage by removing most of the cats.

Several conservation groups, including the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Birds Australia, said the eradication effort did not go far enough and that the project should have taken aim at all the invasive mammals on the island at once.

"It would have been ideal if the cats and rabbits were eradicated at the same time, or the rabbits first and the cats subsequently," said University of Auckland Prof. Mick Clout, who also is a member of the Union's invasive species specialist group.

Clout and others said the Macquarie case illustrates the struggle that Australia and New Zealand have had trying to remove invasive species from their islands, mostly in a bid to protect seabird populations. They have targeted dozens of islands over the past few decades with mixed success.

Cats were removed from Little Barrier island off New Zealand, but it took a second campaign against a growing rat population. On the remote Campbell island off New Zealand, authorities successfully removed sheep, cattle, cats and rats in one of the biggest eradication projects to date.

"The whole ecosystem is recovering superbly," Clout said of Campbell island.

Liz Wren, a spokeswoman for the Parks and Wildlife Service of Tasmania, said authorities were aware from the beginning that removing the feral cats would increase the rabbit population. But at the time, researchers argued it was worth the risk considering the damage the cats were doing to the seabird populations.

"The alternative was to accept the known and extensive impacts of cats and not do anything for fear of other unknown impacts," Wren said.

The parks service now has a new plan to use technology and poisons that were not available a decade ago to eradicate rabbits, rats and mice from the island.

The project to be launched in 2010 will use helicopters with global positioning systems to drop poisonous bait that targets all three pests. Later, teams will shoot, fumigate and trap the remaining rabbits, Wren said.

Some of the earlier critics are now behind this latest eradication effort to remove the island's last remaining invasive species.

"Without this action, there will be serious long-term consequences for the majestic seabirds...and for the health of the island ecosystem as a whole," said Dean Ingwersen, Bird Australia's threatened bird network coordinator.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Feral Cats – The arguments against Trap, Neuter, and Release

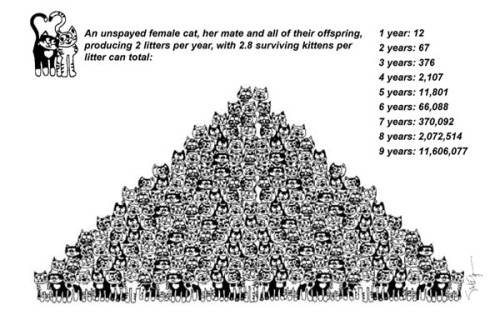

According to the El Paso (Texas) Veterinary Medical Association, Feral Cats are wild, unowned, outside cats that cannot be handled. There are an estimated 120 to 150 million feral cats in the United States. One unspayed female and her offspring can produce 420,000 cats in seven years.

According to the El Paso (Texas) Veterinary Medical Association, Feral Cats are wild, unowned, outside cats that cannot be handled. There are an estimated 120 to 150 million feral cats in the United States. One unspayed female and her offspring can produce 420,000 cats in seven years.New Jersey 04/26/10 nj.com:

(M)any studies show that trap, neuter and release (TNR) programs do not work. They do not protect local wildlife from cats, and they are an ineffective and an inhumane way of dealing with the feral cat problem. They invariably fail to capture and neuter all the cats in the colonies, which also act as dumping grounds for unwanted pets. Colonies, therefore, often grow in size rather than diminish.

Feral cats present a public health threat from rabies, cat-scratch fever, toxoplasmosis and other diseases. Feral cats also typically face unpleasant deaths from predators, disease and automobiles. Hence, feral cats have about one-third to one-fifth of the life span of indoor, owned cats. Perhaps that is why the National Association of Public Health Veterinarians, the Wildlife Society and the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals all oppose TNR programs.

Cats kill an estimated 1 million birds each day in this country, along with a variety of small mammals and other wildlife. Local government policy should develop strong regulations that penalize people for abandoning cats, mandate neuter/spaying, and support pet adoption schemes. California municipalities such as Los Angeles County and Santa Cruz County have had success with such approaches.

Cats kill an estimated 1 million birds each day in this country, along with a variety of small mammals and other wildlife. Local government policy should develop strong regulations that penalize people for abandoning cats, mandate neuter/spaying, and support pet adoption schemes. California municipalities such as Los Angeles County and Santa Cruz County have had success with such approaches.For more information on TNR and cat colonies issues, watch a recent informative video at youtube.com/abcbirds. Darin Schroeder is vice president of conservation advocacy for the American Bird Conservancy

Florida 04/23/10 orlandosentinel.com: From the Journal of Mammology:

Catch-and-release is a familiar concept in fishing, but is more contentious when it comes to cats. To deal humanely with feral cat populations, some advocate a trap-neuter-release approach. Wild cats are allowed to continue living freely, with food provided for them, but have been sterilized and will not continue to reproduce and add to the unwanted pet population.

The April 2010 issue of the Journal of Mammalogy reports a study of feral cat populations conducted on California’s Santa Catalina Island. For more than 20 years the Catalina Island Humane Society has practiced trap-neuter-release at designated “colonies” in Avalon and Two Harbors, the

largest communities on the island.

largest communities on the island.From 2002 to 2004, researchers tracked the movements of 14 sterilized and 13 reproductively intact cats with radio collars in the Middle Canyon and Cottonwood Canyon watersheds on the eastern half of Catalina to determine their home-range and long-range areas.

Contrary to expectations, the study showed that sterilization did not keep the cats “close to home,” defending their territory against the influx of more cats. Both sterilized and intact cats roamed over long distances, traveling between the island’s developed areas and wildland interior.

In places such as Catalina, where ecologically sensitive areas abut urbanized areas, this raises questions about the impact of feral cats on native wildlife. The presence of the cats could threaten efforts to protect vulnerable species and restore native ecosystems. These cats can act as predators and food competitors of native species. With no protection from disease or parasites, the cats are susceptible and can transfer these illnesses to wildlife, humans, and pets.

The feral and stray cat population on Catalina numbers in the range of 600 to 750 animals. Even with a high rate of sterilization, it could take more than a decade for a colony of cats to become extinct. Rather than trap-neuter-release, the authors of this article recommend that, on Catalina, cats trapped in the island’s interior should be removed and delivered to a shelter where they would be adopted or euthanized.

No comments:

Post a Comment