Study takes a look at what happens when wolves, cougars collide

AP photo by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife ¬ This May 25, 2014 photo shows OR-26, a 100-pound adult male, after he was fitted with a GPS tracking collar outside La Grande.

The OSU study examines the interaction of two of the West's iconic predators.

Three of Oregon’s growing wolf packs, perhaps 20 wolves in all, now use parts of the Mount Emily Wildlife Management Unit between Pendleton and La Grande. The same area is home and hunting range for an estimated 100 cougars.

A study underway by an Oregon State University graduate student takes a look at what happens when two of the West’s iconic predators compete for food and habitat.

“Certainly from a science perspective, it’s a really cool study,” said Katie Dugger, an associate professor at OSU who is overseeing the research. Graduate student Elizabeth Orning is conducting the study as her Ph.D. dissertation.

As part of the work, researchers have placed GPS or radio collars on eight cougars and on at least one wolf each from the Mount Emily, Meacham and Umatilla River packs that frequent the area.

On her research website, Orning said increasing populations of large North American carnivores provide an opportunity to study two that share habitat, home ranges and prey.

The steady growth of Oregon’s gray wolf population, which has increased from 14 to 77 confirmed wolves since the end of 2009, made interaction with cougars inevitable.

“We could kind of see this was going to happen,” said Dugger, of OSU.

Although larger than wolves, cougars are likely to fare worse in the competition because they are solitary animals. Wolves travel in packs and can kill adult cougars, compete for deer and elk, chase cougars off carcasses they’ve been feeding on and force them into steeper, brushier terrain, Dugger said.

“We do expect wolves to change the way cougars use the landscape,” Dugger said.

The biggest impact of wolves on cougars might be an increase in cougar kitten mortality, Dugger said. A wolf pack could drive off a mother cougar or force her up a tree while it kills and eats the young or a sub-adult that doesn’t know enough to climb out of harm’s way. At least two cougar kittens are wearing radio collars as part of the study, Dugger said.

The study area is a geographical wildlife unit designated by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, which is collaborating on the research. It includes portions of the Umatilla National Forest and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla reservation.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://newswatch.nationalgeographic.com/2013/12/04/hunters-or-hunted-wolves-vs-mountain-lions/#.VRH0_93xl7k.email

Hunters or Hunted? Wolves vs. Mountain Lions

F109, a six-year-old cougar, nursing three three-week-old kittens.

She wears a Vectronics satellite collar which allows researchers

to follow her movements in near real time and study the secret

lives of mountain lions. Photograph by Mark Elbroch/Panthera

Wolves are coursing, social predators that operate in packs to

select disadvantaged prey in open areas where they can test

their prey’s condition. Mountain lions are solitary, ambush

predators that select prey opportunistically (i.e., of any health)

in areas where slopes, trees, boulders, or other cover gives

them an advantage. Thus, wolves and cougars inhabit and

utilize different ecological niches, allowing them to spatially

and temporally coexist; nevertheless, in the absence of wolves,

cougars utilize areas traditionally assumed to be the sole

dominion of coursing wolves. This suggests that where

wolves are sympatric with cougars, wolves limit mountain lions.

In fact, wolves kill mountain lions. This has never been

disputed. Wolves are considered the dominant competitors

in most interactions between the species. Take for instance,

the Hornocker Institute study of mountain li

ons in Northern Yellowstone led by Dr. Toni Ruth, in which

researchers discovered the remains of three mountain lions

killed by wolves. What is contentious is the idea that

mountain lions might kill wolves.

Look carefully for the mountain lion in the background, pushed

off its kill by a large wolf caught on remote camera. Photograph

courtesy Teton Cougar Project/Panthera

Liz Bradley, a Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks wolf biologist,

reports that she has discovered five wolves killed by mountain

lions in three years—all bearing the characteristic canine

punctures in their skulls betraying the identity of the perpetrator.

Some dispute her claims and point out that wolves fight each

other too, especially adjacent packs, and that they also attack

the head; skeptics believe a canine puncture in a wolf skull

could be made by another wolf just as easily as a mountain lion.

The Teton Cougar Project operates in the Southern Yellowstone

Ecosystem, and is one of very few long-term studies of mountain

lions. Since the start of the project, wolves have trickled into the

area, established territories and reproduced. In 2001, U.S. Fish

and Wildlife Service surveys estimated that there were about 10

wolves in our study area, and that number steadily increased to

as high as 91 in 2010. To date, we’ve documented five lions

killed by wolves, all kittens, and all less than six months old

while they were still relatively slow to climb and less than fully

coordinated. But it was just last October that we finally

documented the contrary. For the first time, a mountain lion

we were tracking killed a wolf.

She’s a particularly feral mountain lion, F109, an adult

female with three three-month-old kittens. All cougars

are feral, of course, but there’s something unique about

F109. She has “crazy” eyes, and always wanders the

most rugged, inhospitable terrain. She was near impossible

to catch in the first place. She’s a survivor.

We can’t tell you exactly what happened, but we can describe

what we deciphered from the clues left behind in the snow

. F109 was up high traversing steep, barren slopes, where

we expected there was little game. Nevertheless, her location

data indicated that she’d stopped and we suspected she’d

made a kill. We slogged up the mountain to investigate, the

ground bare of snow adjacent the road, but as deep as our

thigh in the high bowl where she lingered. The entire area

preceding her position was a mosaic of wolf tracks and trails.

A wolf pack made up of adults, subadults and pups had

criss-crossed the area, leaving barely a patch of snow without

their sign.

Perhaps the wolves had challenged F109, or perhaps just

one of them wandered too close to her kittens, or perhaps

a pup felt like exploring on its own—trying to decipher the

absolute pandemonium of tracks was beyond us. Whatever

the circumstances, F109 captured and killed a pup born this

year just above the chaos of wolf activity. By this time (November),

wolf pups are sizable, their skulls larger than those of coyotes.

We discovered the signs of struggle, the telltale blood in the

snow, and the pup’s remains beneath a lonely subalpine fir:

a pile of coal black fur, bone shards from the legs, and the

skull, skinned but completely intact. F109 and her kittens

had consumed the pup completely.

Thus far, our research has supported exactly what everyone

expected: Wolves dominate mountain lions in most

encounters. But, this recent exchange is particularly

exciting. No longer can we say that wolves dominate

mountain lions in all encounters. What circumstances

led to F109 turning the tables, we do not know. Perhaps

F109’s predecessors served as naïve intermediaries

relearning to coexist with a dominant competitor, a

species absent since 1926, when the last wolf was

killed in Yellowstone National Park. Perhaps F109 is

evidence that lions learn quickly and adapt, and that

mountain lions will successfully coexist with wolves

in the Yellowstone Ecosystem for generations to come.

Source: http://newswatch.nationalgeographic.com/

2013/12/04/hunters-or-hunted-wolves-vs-mountain-lions/

Find more on: http://www.outdoorhub.com/news/

researchers-find-evidence-mountain-lion-predation-wolves/

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Interactions between cougars (Puma concolor) - Dennis Murray's ...

-

dennismurray.ca/pdf/Kortello%20et%20al.%202007.pdf

Cougars (n =13) and wolves (n= 8 in 2 packs) were monitored intensively over 3 winters (2000–2001 to 2002–2003) via radio telemetry and snowtracking. We documented a 65% decline in the local elk population following the arrival of wolves, with cougars concurrently switching from a winter diet primarily constituted of elk to one consisting mainly of deer and other alternative prey. Elk also became less important in wolf diet, but this latter diet switch lagged 1 y behind that of cougars. Wolves were responsible for cougar mortality and usurping prey carcasses from cougars, but cougars failed to exhibit reciprocal behaviour. Cougar and wolf home ranges overlapped, but cougars showed temporal avoidance of areas recently occupied by wolves. We conclude that wolves can alter the diet and space use patterns of sympatric large carnivores through interference and exploitative interactions. Understanding these relationships is important for the effective conservation and management of large mammals in protected areas where carnivore populations are recovering.

Wolf and Cougars Populations - Both Sexes of Cougars in the Area and Wolf Packs as Small as 2 Individuals at the Beginning and End of the Study

As you can see, both male and female cougars were in the area and the wolf pack size was 2 in 1999 (beginning of the study), rising to 15 (increase likely due to pups/younger animals) in 2001, and then dropped to 7-10 in two packs in 2003 (at the end of the study).

However, the wolves usually present at the end of the study in 2003 numbered only 2. This is from the related PhD thesis from the author, which provides additional details.

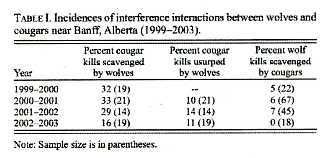

Interactions at Kill Sites - Wolf Pairs Appear to Dominate

Below is a summary of interactions at kill sites and the authors' analysis from the PhD thesis. In 1999 when only a wolf pair lived in the area, they scavenged 6 (32%*19) cougar kills and cougars only scavenged 1 (5%*22) wolf kill. Neither species was observed to steal the other's kill that year. In 2002-2003 when only a wolf pair was likely present, they scavenged 3 (16%*19) cougar kills and cougars scavenged 0 wolf kills. The wolves stole 2 cougar kills (11% * 19) and cougars stole no wolf kills.

Apparently, cougars were reluctant to return to cougar kills that were scavenged by wolf pairs as well.

In 2001, when the wolf pack reached 15, a cougar was killed.

IMHO, a wolf pack is more likely to catch a cougar and this is why this occurred then, but obviously there is less risk with more animals present (though I stress most of these animals would have been pups or yearlings).

No comments:

Post a Comment