The mysterious mountain lion still roams Texas, but has it come to Dallas?

In October 2014, a trail camera snapped a grainy photo of a young mountain lion lurking around a deer feeder near Glen Rose, about 50 miles southwest of Fort Worth.

In August of last year, Brookhaven College in northwest Dallas County sent out an unusual warning: A mountain lion had been spotted on campus and students should take caution.

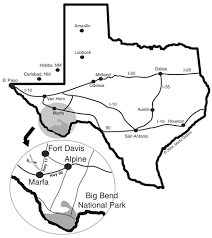

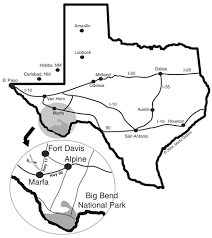

Southwest Texas where Big Bend State Park

and the Davis Mountains exist, is the breeding home

of Texas Pumas

A month later, residents of Steiner Ranch just outside of Austin filed two reports of mountain lion sightings along a trail head in the wooded community.

Southwest Texas where Big Bend State Park

and the Davis Mountains exist, is the breeding home

of Texas Pumas

A month later, residents of Steiner Ranch just outside of Austin filed two reports of mountain lion sightings along a trail head in the wooded community.

In May, a woman called authorities to report that a mountain lion had attacked and killed her daughter’s horse near Cleburne, just an hour south of Dallas.

Of all the wild things that wander Texas, none comes close to the mystery of the mountain lion. People see them where they are not. They don’t see them where they are.

Each year, the state receives dozens of reports of sightings. But only a handful are verified, and none in the urban sprawl of Dallas and Fort Worth.

A taxidermist in Glen Rose mounted this mountain lion that Wesley Monk shot and killed in October 2014 while deer hunting in Somervell County, about 50 miles southwest of Fort Worth. A game warden said at the time that it was the first mountain lion killed in the area in a dozen years.(Steve Leech photo)

Wesley Monk (left) shot a mountain lion while deer hunting in Somervell County, about 50 miles southwest of Fort Worth, in October 2014. With him was Steve Leech, a taxidermist with Hoof and Horn Taxidermy of Glen Rose.

(Steve Leech)

Yet mountain lions do exist in Texas, and they wander far and wide. But do they venture as far north as North Texas, creeping up the riverbeds, prowling for wild hogs and deer?

The answer is that no one seems to really know. Perhaps there is a mountain lion here. And perhaps there isn’t.

Nevertheless, the descriptions and witness reports keep coming and describe an otherworldly being: a spectral creature, eyes glowing, gliding through the night.

There is a deep and almost primal interest in the mountain lion that seems to drive us to want to see it, even when it isn’t there. “It’s a rare and mythical creature that’s fascinating to people,” said Jonah Evans, state mammalogist for Texas Parks & Wildlife, who collects data on mountain lions for the state.

When people do see them, the experience is usually lightning-fast and unforgettable.

In April, in Pescadero, Calif., a woman described how “the shadow of an animal” crept through an open door into her bedroom, snatched her dog from the foot of the bed and disappeared into the darkness. DNA testing of saliva mixed in the dog's blood would confirm the shadow was a mountain lion.

But in this part of the world, the mountain lion is more myth than reality.

A 2015 photo from a game camera required an on-site visit from urban wildlife expert Chris Jackson to conclude whether it shows a mountain lion or a bobcat.

(David Walker/DFWUrbanWildlife.com)

Chris Jackson looks for wildlife at the Village Creek Drying Beds in Arlington. The old wastewater treatment facility has been overtaken by foliage and wildlife, and it's a popular bird spotting location.

(Ryan Michalesko/Staff Photographer)

This cat wasn’t seen somewhere along a rocky ridge in Southwest Texas, where you’d expect to find mountain lions. The photo was taken along a greenbelt park in Garland.

If Jackson could confirm the sighting, he knew it would create a stir locally unlike any other animal.

From the time Jackson created his website 12 years ago, he noticed the powerful draw mountain lions have on our imagination. Now 49, and a software engineer by day, Jackson has spent the intervening years observing, photographing and writing about wildlife in one of the most densely populated regions in the country.

Five years ago, he posted an image of a mountain lion with the plea: “If you see one of these ANYWHERE in North Texas please report it to me.”

Reports rolled in; most lacked verifiable information or amounted to secondhand information heard from a neighbor. Or the animal in question was obviously a bobcat or house cat.

Two years ago, he noted he’d been getting “an unusual number” of mountain lion sightings from around the Dallas area. He had to balance his excitement with the skepticism of someone steeped in an engineer’s methodical and analytical approach to new information.

Bottom line: He knew that a mountain lion in North Texas would be an extremely rare occurrence but not outside the realm of possibility.

On a recent drizzly morning, he left his camera behind and carried only a pair of binoculars. During a two-hour hike along the berm of the drying beds, he spotted a raccoon thrashing in tall grass under the watchful gaze of a cooper hawk perched statue-like on a tree limb. He spied several ibises, identifiable by their black-tipped wings as they flew overhead. And down on the ground, he pointed out a black-bellied whistling duck floating near a black-necked stilt, easily recognized by its long, pink legs and thin, black bill.

Not bad for a Saturday in early July. But has he given up hope of seeing a mountain lion?

“I will admit that I’m a little more cynical about it now than I was when I started out,” he said. “I’ve been working for years to tamp down the rumors. But I absolutely haven’t given up hope.”

He can easily imagine a scenario in which a transient mountain lion, a young male, moves out of West Texas in search of a mate and makes his way to North Texas, following prey down the Trinity River and into the metro area.

“What we do have in the metroplex is an abundance of the mountain lions’ favorite game, which are deer and feral hogs,” living in the Trinity River bottoms, he said.

Texas wildlife officials have also received a dozen or so reports of sightings from around North Texas since 2011. Most are probably false alarms, said officials with Texas Parks & Wildlife, which sends wardens out to check up on reports of mountain lions only when people or livestock are threatened, such as the report of the horse mauling in Cleburne a few months ago.

They were able to confirm one sighting on the edge of North Texas. On Oct. 23, 2014, a trail camera snapped a photo of what was unmistakably a male mountain lion in Somervell County, southwest of Fort Worth and near Glen Rose.

Hunter vs. mountain lion

Seven weeks later, on a misty December morning, Wes Monk, 35, a mechanic who lives an hour’s drive from Fort Worth, was hunting deer on private property near Glen Rose. Suddenly, he noticed a disturbance coming from the trees. “The crows were going crazy,” he said.

When he went to record the birds on video, his attention was drawn to something by the deer stand. That’s when he saw it. “Good Lord, have mercy,” he said to himself. “That’s a mountain lion!”

Monk stared at the animal in shock. He decided if he didn’t shoot it, nobody would believe him. “I’d just be another story of someone who got a glimpse of one,” Monk said.

With a single shot from his .243 rifle, he felled the cat. It weighed a little over 100 pounds and was about 5 feet long. A local taxidermist, Steve Leech, mounted the animal. He refused to believe Monk had shot a mountain lion until the hunter texted him the photo. In Leech’s experience, too many people had called a bobcat a mountain lion.

In Texas, mountain lions aren’t protected and can be killed anytime or anywhere it’s legal to discharge a firearm, Jackson said. But even though it was legal, Jackson couldn’t disguise his disappointment over the outcome.

“This one guy got to decide for the rest of us whether we got to have a mountain lion here in the area or not,” he said.

Monk said he respected the views of conservationists. “It would be nice to see mountain lions whenever you go out in the woods,” he said.

Monk still hunts. He plans to be out again this deer season. And he believes somewhere in those same woods and hills, there’s another mountain lion roaming.

“There’s no doubt in my mind,” he said. “Not a doubt at all.”

------------------------------------------------------------------

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=3&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwiN1sqJv_3UAhUI4SYKHf5cBjIQFggwMAI&url=https%3A%2F%2Ffronterasdesk.org%2Fcontent%2F9831%2Ftracking-mountain-lions-texas-study-suggests-population-stable&usg=AFQjCNFolHY1OXlggelRSXARMIKFtSskFATracking Mountain Lions In Texas: Study Suggests Population Is Stable

October 30, 2014

Wildlife biologist Dana Milani and landowner Bert Geary examine an adult female mountain lion. Geary is one of more than 50 landowners who've granted access to their land to study an animal that has been the historical object of scorn by many Texas ranchers.

Price Rumbelow

The mountain lion of Texas is known by many names in the Southwest. Cougars, panthers and pumas to name three.

In California it’s protected. In Arizona and New Mexico, you can hunt this predator, but with strict limitations. In Texas, mountain lions can be hunted at will. Still, preliminary results from a four-year-old study suggest that the Texas mountain lion population is stable and may be growing.

Data from a Texas project tracking mountain lions by satellite imply a population of between 25-40 animals in one of the sky islands in Texas. Sky island refers to a mountain range surrounded by flatlands or in the case of this study, the high desert that's a 90-minute drive north of the U.S.-Mexico border.The project, privately funded by individuals and nonprofit foundations, is an initiative of the Borderlands Research Institute (BRI) at Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas.

The Sky Island region of West Texas--Big Bend State Park and

Davis Mountain region

The Sky Island region of West Texas--Big Bend State Park and

Davis Mountain region

This Texas mountain lion died after stepping into a metal snare laid down by a ranch owner who wants to eliminate mountain lions. Some ranch owners maintain that lions should not be studied but be killed. This image was taken October 18, 2014 in Brewster County, Texas by a trapper employed by the ranch owner. The trapper did not wish to be identified

What separates this project is that it takes place on private land, an accomplishment in a state where 95 percent of the land is in private hands. What’s more, most of the test area is owned by ranchers, many of whom have harbored revulsion for the mountain lion.

“You have to understand the values that people have, the history that they (ranchers) have, the culture that they have," said Louis Harveson, the leader of the research team.

That history is marked by a loathing for the animal, the notion that mountain lions should be killed on sight. Yet Harveson’s managed to get more than 50 ranchers and other landowners to open their gates to his research team. Harveson assured ranchers that no lions would be brought in from other regions, only that the existing population in the Davis Mountains of west Texas would be studied. He also asked ranchers to consider the animal’s role in maintaining nature’s checks and balances.

“Mountain lions are the apex predator, just like sharks and oceans," said Harveson.

"There’s a food chain that’s in existence," he explained. "And that apex predator symbolizes wildness. This animal that’s able to kill a deer a week or a large prey item a week, that just says that there’s a good healthy ecosystem intact.”

In four years, Harveson’s team has used leg snares to capture 22 mountain lions, tranquilize them and place satellite and VHF radio beacons on their collars.

James King is a landowner whose family has deep roots in ranching. He’s allowed the research team on his land to record details of the animals’ diet.

“The kill sites are detectable by the fact that the lions don’t move with these GPS collars," said King, referring to the GPS location beacons. When the signal remains fixed on a location, it means one of two scenarios are unfolding.

Either the animal has died, or the stationary signal suggests that the lion has stopped at a kill site, a place where the animal eats its prey.

Wildlife biologist Dana Milani is a member of the research team. She crosses canyons and sepia-toned mountain ridges every working day. She documents the lions’ appetite for deer, rabbit and porcupine. That appetite keeps those lower-level species in check.

“You’re always trying to be quiet to stress the animal less," she said while moving through underbrush.

She said she has been fortunate lately given how elusive the mountain lion is. Milani recently checked and helped collar two adults, a female and a male. She took samples of blood and tissue for genetic analysis before withdrawing and letting the sedation wear off.

A female adult wakes up after the sedation wears off. She's outfitted with satellite and VHF tracking beacons on her collar.(Patricia Harveson credit)

She said without the support of ranchers and other landowners, she could not paint a picture of how lions sometimes help ranchers.

A case-in-point, James King has trouble eliminating feral hogs. That’s an invasive species brought to the Americas by Christopher Columbus.

“I shoot a lot of feral hogs and they’re hard to exterminate. And those lions are out there at night doing that job," he said with a wide smile.

King said the antipathy toward the mountain lion goes back to the days when sheep and goats were raised in this part of the Southwest. Today, King said, ranchers principally raise cattle. He said he's encouraged by one development profiled in the study.

"Here in the Davis Mountains, we’re not seeing any kills of domestic cattle," he said.

"We’ve documented over 200 different kills," said project leader Harveson. "And not one domestic animal has fallen to mountain lions and that’s a fact.”

Across the Southwest, attitudes toward the predator may be changing.

Private landowners in Arizona have just agreed that a 10-mile corridor traveled by lions will be protected. In California, a new UC Davis study suggests migration corridors be created to avoid lions being hit on the highway.

James King said he’s not an evangelist for mountain lions. But like many of his neighbors, King simply wants information about the animal.

“Let’s give these scientists access so they can help us understand the movement, the population, their whole dynamics so we can be better land managers," King said.

The leaders of the Texas study said they don’t want to influence policy. They just want to gather data so that policymakers and area ranchers can make informed decisions on mountain lion management.

No comments:

Post a Comment