Are Large Carnivores Doomed by Climate Change?

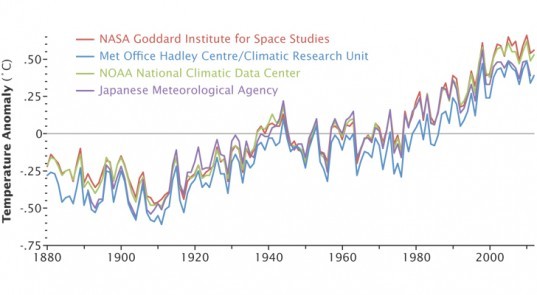

The world is getting warmer, creating an extinction threat for many species. According to NASA, since 1880 the Earth's global temperature has risen by nearly one degree Celsius. However, not all species are equally affected by climate change. And as wildlife biologists such as Aldo Leopold discovered nearly a century ago, not all species are equally important ecologically. Large carnivores play a lead role in maintaining resilient, biodiverse ecosystems because they control their prey, which indirectly improves habitat for other species. Today, some of these ecologically powerful carnivores are highly vulnerable to climate change.

Global Warming Since 1880, Courtesy NASA

In our rapidly warming world, species have two choices: they can adapt or go extinct. A species' natural history determines its ability to adapt--and its extinction risk. This means that a "generalist" species with a high reproductive rate, high dispersal, and a diverse, flexible diet can adapt more easily than a species with a low reproductive rate, low dispersal, and a restricted diet.

Additionally, how we manage wildlife contributes to extinction. Hunting and trapping (called "take") puts additive pressure on species already facing survival challenges due to climate change. According to ecologist Scott Creel, the rapid worldwide decline of large carnivores that are hunted and trapped is of high concern because of the negative consequences this has on ecosystem structure and function.

Large carnivore species vulnerable to climate change share some key traits. These bellwethers are solitary individuals that have a low reproductive rate, high intra-species competition, and a Northern Hemisphere distribution. On the other hand, species relatively impervious to global warming, such as the wolf and coyote, have a high reproductive rate, broad diet, and can thrive in diverse habitat from deserts to mountains. Similarly, the cougar and jaguar, which have broad dietary and habitat needs, don't face serious climate-related threats.

Jaguar (Panthera onca), Photo Courtesy AZFG

Here I present an overview of some of the carnivore species for whom climate change presents a significant challenge. I look at their extinction risk by the year 2100, the typical benchmark used to gauge global warming impacts.

Lynx (Lynx canadensis), Photo Courtesy USDA

The lynx, an obligate carnivore (meaning it can only derive nutrition from meat) whose numbers are low globally, must have young forest with diverse structure for hunting and mature forest for denning. It can adequately nourish itself only by eating snowshoe hare--its primary prey--and often starves to death when it switches prey. Snow and dispersal improve its hunting success. Given its low reproductive rate and strict habitat and food needs, the lynx has low resiliency and high extinction risk by 2100.

Wolverine (Gulo gulo), Photo by Jeff Copeland

The wolverine, a wide-ranging obligate carnivore that has experienced historical and recent widespread declines, primarily scavenges the meat of dead animals and opportunistically hunts small mammals and hooved animals. It needs year-round snow for denning and has a low tolerance for heat. Given the rapidly diminishing global extent of year-round snow, even in mountainous regions, and the wolverine's low resiliency as a species, it has high extinction risk by 2100.

Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos), Photo by Cristina Eisenberg

The grizzly bear, a wide-ranging omnivore whose population has been increasing in areas where it is protected, can eat over 270 different foods. However, this species needs high protein (e.g., pine nuts) at critical times, such as prior to hibernation. Global warming is negatively impacting availability of key foods. While the grizzly bear's low reproductive rate limits its resiliency, its diverse diet will enable it to adapt to climate change. If it continues to be protected, it faces low extinction risk by 2100.

Polar Bear (U. maritimus), Photo by Cristina Eisenberg

The polar bear, an obligate carnivore in rapid decline globally, has strict habitat and food needs and a low tolerance for heat. This polar marine species' primary prey is the ringed seal, which it can kill effectively only on ice. Additionally, it requires a high-fat diet that only seal meat can provide. Due to its low reproductive rate and dependence on ice (which is shrinking fast worldwide), the polar bear has low resiliency and high extinction risk by 2100.

What can we do to improve their future? While it goes without saying that we should do all we can to reduce our carbon footprint, the positive impacts of such action will take centuries to manifest fully. That's not fast enough to save species like the polar bear that face immediate extinction.

There are more direct actions we can take. First, we can cease hunting and trapping these animals. By eliminating their take, we can buy them precious time to adapt to climate change. Second, we can improve their habitat. Reducing or eliminating timber harvest and snowmobile use in sensitive lynx denning sites can help increase their reproductive success. Third, we can maintain permeable landscapes that allow dispersal via crossing structures (overpasses, underpasses) on busy highways. Finally, assisted migration (e.g., translocating wolverines from lower-elevation mountains, such as the Northern Rocky Mountains, to higher-elevation mountains, such as the Southern Rocky Mountains) can help.

Animals' Bridge Wildlife Overpass, Flathead Reservation, Montana, Photo by Cristina Eisenberg

So are large carnivores doomed by climate change? It depends. If we continue to do business-as-usual, which includes hunting and trapping, some species, such as the wolverine and polar bear, are more doomed than others. Yet we have the scientific knowledge to conserve at-risk carnivores using responsible management that gives them time to adapt and room to roam. The remaining question is, do we have the wisdom and maturity as a society to do so?

* * *

Learn more about carnivore conservation by reading The Carnivore Way: Coexisting with and Conserving North America's Predators, and The Wolf's Tooth: Keystone Predators, Trophic Cascades., and Biodiversity by Dr. Cristina Eisenberg. Learn more about large carnivore ecology by joining Cristina afield on her Earthwatch field research expedition, Tracking Fire and Wolves through the Canadian Rockies.

Follow Cristina Eisenberg on Twitter: www.twitter.com/ceisenbec

No comments:

Post a Comment