Blue Jays in Winter

“Jay, jay, jay!” Every morning last winter I awoke to the loud cries of a flock of 17 blue jays dancing around my feeder. They gorged on sunflower seeds and suet, scaring away smaller birds, then left, only to return in the afternoon. I ended up buying a second feeder for the smaller birds, which was more difficult (though not impossible) for the jays to feed from.

“Jay, jay, jay!” Every morning last winter I awoke to the loud cries of a flock of 17 blue jays dancing around my feeder. They gorged on sunflower seeds and suet, scaring away smaller birds, then left, only to return in the afternoon. I ended up buying a second feeder for the smaller birds, which was more difficult (though not impossible) for the jays to feed from.

This boisterous group was a foraging flock. Like many species of birds, blue jays change their behavior from summer, when breeding birds live in pairs, to winter, when they often gather in groups. In summer, blue jays feed and raise their young mostly on insects, while in winter, they shift to fruits, nuts, and seeds. As biologist Bernd Heinrich explained in his book Winter World, these food sources are widely dispersed, but occur in large clumps that groups of birds can detect more easily by combining their scouting efforts. Another advantage of winter flocks is that many eyes are better for detecting predators.

Most blue jays in the Northeast stay in the same area year-round. An analysis of data from 8,000 recaptures of almost 102,000 banded blue jays from three northeastern states found that 89% of the population was non-migratory, while 11% travelled to southeastern states for the winter. Large flocks of migrating jays have been observed along the Great Lakes and Atlantic Coast.

Some jays in the study migrated south some years, but remained on their breeding grounds other years. Birds that stayed for the winter were found in widely separated locations in different years. Much is unknown about the reasons blue jays migrate when they do, but the variability in their movements may be related to fluctuations in important mast crops, such as acorns and beechnuts.

Nuts are a favorite food of blue jays and they will cache them for later use. Bill Hilton, who studied blue jays in Minnesota for three years, observed jays gathering as many as four red oak acorns in their crops (a pouch in the esophagus), flying to other locations, scratching small holes in the ground, and burying the nuts. His jays flew as far as a mile to cache acorns. Since jays don’t retrieve all the nuts they bury, they aid in the spread of oak and beech trees. In fact, blue jays have been credited with accelerating oak expansion northwards after the last glaciation.

Jays also store other food. In Ravens in Winter, Bernd Heinrich described watching a pair of blue jays peck off pieces of meat and fat he had put out for ravens near his cabin in Maine. The jays hid the meat in trees in the woods nearby, making 127 caches in one day. They did not call frequently and chased other jays away. Heinrich speculated that the jays’ behavior at a novel food source might be different than at more common foods, around which they’re typically more tolerant of other jays.

Blue jays, members of the big-brained corvid family that includes ravens and crows, are known to be inquisitive and to adapt their behavior to new situations. For example, captive jays in a lab tore off scraps of the newspaper lining their cages and fashioned tools to rake in hard-to-reach food pellets. Jays will also imitate the calls of hawks to scare off other birds.

A winter flock of blue jays is likely to have a dominance hierarchy, or “pecking order” of individuals, which determines who gets the first crack at food. Once social rank is established, conflict among individuals and the energy devoted to squabbling is reduced. A three-year study of a winter flock in Massachusetts found that the group remained distinct from neighboring flocks and many jays returned to the group in successive winters.

This year, a blue jay kicked off bird-feeding season at our house before Thanksgiving by pecking at the Indian corn I had hung on our front door. For a while, every time I heard it, I opened the door and shooed the bird away. But the jay was more persistent than I was. It had consumed half the kernels before I gave up and moved the bundle of corn to the backyard. There has been no sign of the 17 member flock that came to the feeder last year, but a group of four jays visits our feeder regularly. Their striking blue plumage and raucous cries brighten up bleak winter days.

Susan Shea is a naturalist, writer and conservation consultant who lives in Brookfield, Vermont. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.

---------------------------------------------

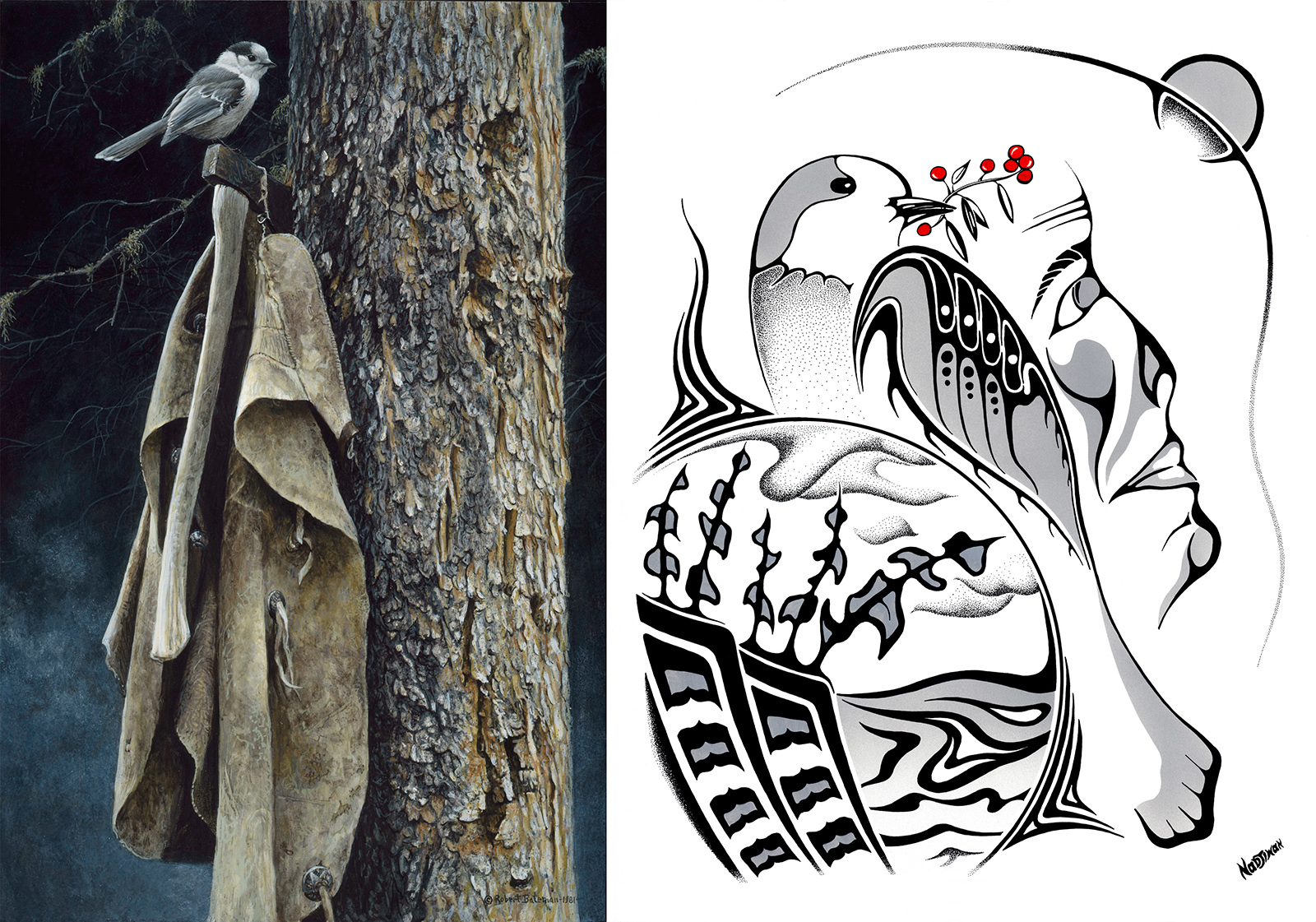

Meet our national bird: the gray jay

After two years, nearly 50,000 votes and thousands of public and expert comments, the Canadian Geographic National Bird Project concludes. Meet our newest national emblem.

Historically the companions of First Nations hunters and trappers and European explorers and voyageurs, gray jays are today common visitors in mining and lumber camps and research stations, and follow hikers and skiers down trails in provincial, territorial and national parks

-----------------------------------------------

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/California_Scrub-Jay

California Scrub-Jay

These birds are a fixture of dry shrublands, oak woodlands,

and backyards from Washington state south to Baja California.

No comments:

Post a Comment