When Animals Grieve

Scientists are uncovering evidence that humans are not the only animals that mourn their dead

A most extraordinary event in Yellowstone. A bison cow had earlier been killed by wolves. Just as we were driving past the carcass, 12 huge bulls began to surround her and pay homage. They grunted, pawed the ground and were visibly upset. Most faced towards her with heads bowed low. One male continuously licked her lifeless body. This circle of grief went on for half an hour. They mourned her death. Then, one by one, each slipped away. A professional photographer near us explained only few animal groups pay tribute to their dead in this way. One other is elephants. We all sat in silence and watched. It was a sacred, moving, somber and beautiful moment

Rich emotional lives

“The lower animals, like man, manifestly feel pleasure and pain, happiness and misery,” Charles Darwin wrote in 1871. “So intense is the grief of female monkeys for the loss of their young, that it invariably caused the death of certain kinds.”

An adult striped dolphin of unknown sex attends a dead adolescent female in the Gulf of Corinth, Greece, seemingly trying to keep it afloat.

Darwin’s view—that species beyond humans have rich emotional lives—did not evolve into scientific consensus. “In the 20th century, the predominant paradigm was human exceptionalism, the idea that animals are pretty robotic,” says Barbara J. King, emerita professor of anthropology at the College of William and Mary and author of the 2013 book How Animals Grieve, a comprehensive synthesis of animal mourning research. “The thinking was that animals live in the present; they’re solving their problems for survival; they don’t feel a whole a lot.”

There were exceptions to this view. In 1972, the late Yale University biologist and anthropologist Ursula Moser Cowgill reported that two small captive primates called pottos, whom she described as “depressed,” set aside food for a dead companion even at the risk of starving themselves. Around the same time, in Tanzania, Jane Goodall observed how a young chimpanzee called Flint stopped eating and grew gaunt and lethargic after his mother Flo’s death. He died a month later. “His whole world had revolved around Flo,” the primatologist wrote, “and with her gone, life was hollow and meaningless.”

In Kenya’s Maasai Mara, an African elephant calf gently touches the skull of a dead adult. While most animals—even species thought to mourn—lose interest in a body after it decomposes, elephants famously pay homage to the bones of their kin. For two days, a western lowland gorilla (below) cradled and groomed her stillborn infant. “She tried to revive it, but she couldn’t,” says photographer Anup Shah. He and Fiona Rogers spent weeks documenting this gorilla’s family in the Central African Republic.

Even today, many researchers stay away from the language of emotion. “‘Grieving’ is a word that is perceived as illegal among scientists,” says biologist Giovanni Bearzi, president of Dolphin Biology and Conservation, a nonprofit research organization based in Italy. “Our capability of understanding what happens from an animal’s standpoint is pretty limited.”

Some scientists question whether a creature can mourn without a notion of mortality. “You have to understand ‘I am alive’ to understand that someone is dead,” says Alex Piel, a primate biologist at England’s Liverpool John Moores University. “That’s where we run into problems: Most animals, as far as we know, don’t have consciousness.”

After her calf died on a Kenyan savanna, this Rothschild’s giraffe stood vigil by the body, lingering for days without eating or drinking. “She was just standing guard over her dead baby,” says the biologist who observed and photographed the animal.

That argument exasperates Carl Safina, an ecologist at Stony Brook University and author of Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel. “There are many animals who, in an operative sense, understand death,” he says—for example, predators who must understand the difference between alive and dead when they kill their food. Besides, he says, “humans have many concepts of mortality—karmic wheels, eternal life and so on—most of which conflict, which indicates most of them are wrong.” Yet we all grieve.

King says that over the past few years animal-grief research has “exploded”—part of a larger “animal turn” among academics who advocate broadening the range of lives and cultures that are studied. Technology has helped, too, including remote monitoring cameras at wildlife sanctuaries. “We have access to behaviors that we didn’t before,” Piel says. In this changing climate, more scientists are publicly making the case for animal grief.

Upsurge of science

Zoe Muller, a University of Bristol wildlife biologist who founded the Rothschild’s Giraffe Project in Kenya, recalls a morning in 2010 when she came upon 17 female giraffes running haphazardly and looking distressed in a part of the savanna they don’t normally frequent. It turned out an injured calf had died, and the adults had gathered with its mother. They stayed with her for two days, frequently nudging the dead animal with their muzzles.

On the third morning, Muller returned. The mother appeared to be alone, standing alert in the shade of an acacia tree. On closer inspection, the biologist realized that hyenas had moved and fed on the calf’s carcass. “The mother was still standing over the body,” she recalls, “even though it was half-eaten.” Though giraffes feed almost constantly, “she wasn’t eating. She wasn’t drinking. She was just standing guard over her dead baby.”

Muller interpreted the giraffe’s behavior as grief. At the time, though, she was reluctant to say so publicly, knowing that “some scientists are very strict about not anthropomorphizing.” Since then, “my personal stance has changed. I would now be a lot more open about acknowledging nonhuman grief. Giraffes, humans, we’re all mammals. Our system of emotion is largely driven by hormones, and hormones are likely to have evolved similarly in all mammals.”

Nudging a dead female, a male Burchell’s zebra is “trying to wake her up,” suggests photographer Christophe Courteau. While scientists have not documented grieving in zebras, the number of such examples is growing.

One way to study grief, then, is to measure changes in hormone levels of survivors. That’s what behavioral ecologist Anne Engh realized when she was studying chacma baboons in Botswana’s Okavango Delta. One of those baboons, an older, high-ranking female called Sylvia, had earned the nickname Queen of Mean. “She went out of her way to be obnoxious to the other females,” says Engh, who now works at Kalamazoo College. “She would threaten somebody just because they’re there, and because she could.”

Sylvia did have one steady companion: her adult daughter Sierra. The duo spent most of their free time together, grooming each other and handling each other’s babies. One day, while Engh was present, lions attacked members of the group as they foraged for tubers in an area of tall grass. Sierra was killed, as was a male with whom she had been consorting. Afterward, Sylvia spent a lot of time alone, staring at her feet. “If she had been a human,” the ecologist says, “I absolutely would have said she was depressed.”

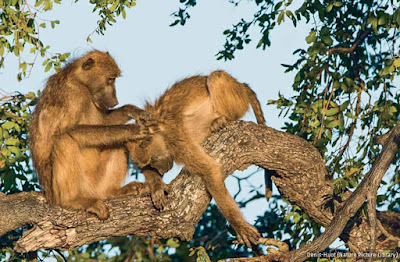

Chacma baboons groom one another more often after the death of a companion, a behavior that lowers stress hormone levels.

That led Engh to review hormonal data on Sylvia and other female baboons that had lost close female relatives—data her team had routinely collected using fecal samples for about a year. What she discovered, and reported in 2006 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, was that even a month after the deaths, females showed significant increases in stress hormones called glucocorticoids. After two months, the levels returned to normal.

Grooming and grief

Engh also discovered that, after their losses, the baboons groomed more frequently and with more partners. (Physical contact stimulates release of the hormone oxytocin, which inhibits glucocorticoid release.) “It seemed like they were actively trying to form new friendships,” she says.

That’s what Sylvia did: After her daughter died, she diversified her own grooming network. “In particular, she focused on a fairly low-ranking female who also didn’t seem to have a close friend at that time. “This is a female that she would have absolutely ignored before,” Engh says. “And along with that, her glucocorticoid levels decreased.”

Is it grief? “I still hesitate a little bit to say,” Engh says. “But you find something similar in humans. If women who lose spouses have support from close female friends, they do have increased glucocorticoid levels, but not as high as females who are more socially isolated. So, there is probably a parallel.”

Not every species lends itself to this type of quantitative research, so the question might ultimately remain unsettled. Still, it fascinates. In 2016, Bearzi was with a group of students from Texas A&M University in Greece’s Gulf of Corinth when they spotted an adult striped dolphin circling a dead adolescent and struggling to keep it afloat. “There was a sense of protecting and trying to resuscitate the animal,” he says— “as if to say, ‘Come on. Let’s swim together. Let’s go back to the group.’”

In moments like this, how do we know what’s really going on? Measuring stress hormones or brain activity might yield valuable data, Bearzi says. “But most of the time it is not possible, and I am not advocating that more invasive research be done on grieving cetaceans.” One alternative, he suggests, might be using underwater microphones to record changes in acoustic behavior.

What Bearzi most remembers from that afternoon in Greece was how visceral everyone’s reaction was. The students had not been trained to think about animal emotions, he says. Yet they described their observations in the language of psychicpain. “It’s becoming exhausted,” one of the students narrated on camera. “It’s putting itself in danger. Self-preservation seems to have momentarily left because it is grieving for its loved one.”

Bearzi had a similar reaction. “As a human being, I can easily relate to animals’ suffering because another animal died,” he says. “And maybe it is not so complicated. Maybe it does have to do with the kind of grieving that we humans feel. It may not be exactly the same, but it looks like it is related.”

In Kenya’s Maasai Mara, an African elephant calf gently touches the skull of a dead adult. While most animals—even species thought to mourn—lose interest in a body after it decomposes, elephants famously pay homage to the bones of their kin. For two days, a western lowland gorilla (below) cradled and groomed her stillborn infant. “She tried to revive it, but she couldn’t,” says photographer Anup Shah. He and Fiona Rogers spent weeks documenting this gorilla’s family in the Central African Republic

The hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae(HWA), a tiny sap-sucking insect related to aphids, is causing widespread death and decline of hemlock trees in the eastern United States. This species, native to Asia and the Pacific Northwest, was first noted in the eastern United States in 1951 in a park in Richmond, VA. The genotype present in eastern

The hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae(HWA), a tiny sap-sucking insect related to aphids, is causing widespread death and decline of hemlock trees in the eastern United States. This species, native to Asia and the Pacific Northwest, was first noted in the eastern United States in 1951 in a park in Richmond, VA. The genotype present in eastern